Wouldn’t it be fun to step into a vast musical environment, full of sounds from across the distance, echoing through the streets and woods – that change their rhythms and order as you walk? To be surrounded by a melody that is created by where you choose to stand? To be a part of an audience that looks more like kids in an easter-egg hunt than a classical concert, exploring the landscape and sharing favorite locations? And finding little gems of precision musicianship and improvisation along the way – all with acoustic instruments and no mics or loudspeakers.

Maybe you’ve noticed how thunder arrives 5 seconds per mile after its lightning strike, or that you have to wait for the boom of a high 4th of July firework, or that the drummers’ sticks don’t match up to their sounds at the halftime show? If you could go back in time to re-live any of those experiences from a different location, you would hear different timings of those same events. Why? Since sound travels at a constant speed, the further you are from the source, the more time it takes to reach you. Distance Music exploits this natural phenomenon to construct this new music experience.

Like a book or movie, music is a story that runs along a planned route, created by its author, director, or composer. Distance Music is more like a modern computer game, where the composer, like a game designer, creates an environment that gives agency to the player, or in this case, the listener, to make their own storyline. Audiences engage by exploring the conditions set up for them by choosing where to walk in its vast concert area, measuring from the hundreds of feet to the tens of acres. The music they hear is the product of their exploration. A stage becomes irrelevant because there is no “best place” to listen to the composer’s intentions.

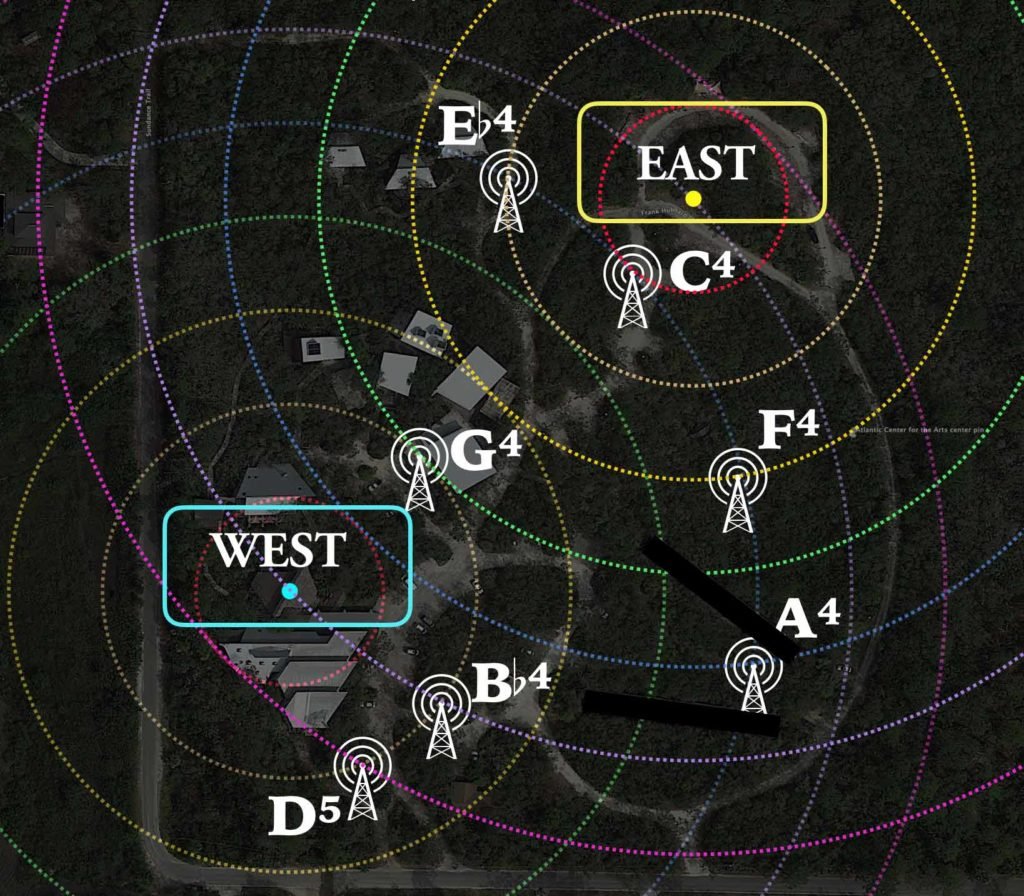

The music has two distinct layers. “Shifting Ground,” which is created by machines and heard across the concert site. “Musician Bubbles” feature live musicians synchronizing with the shifting ground at specially chosen spots.

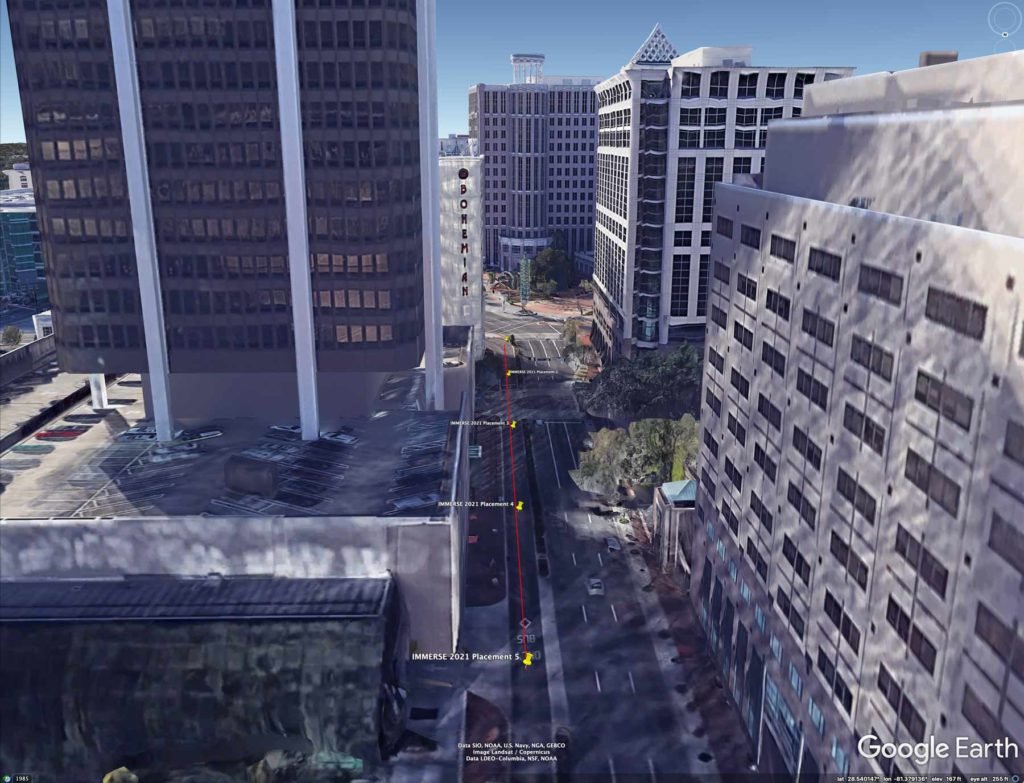

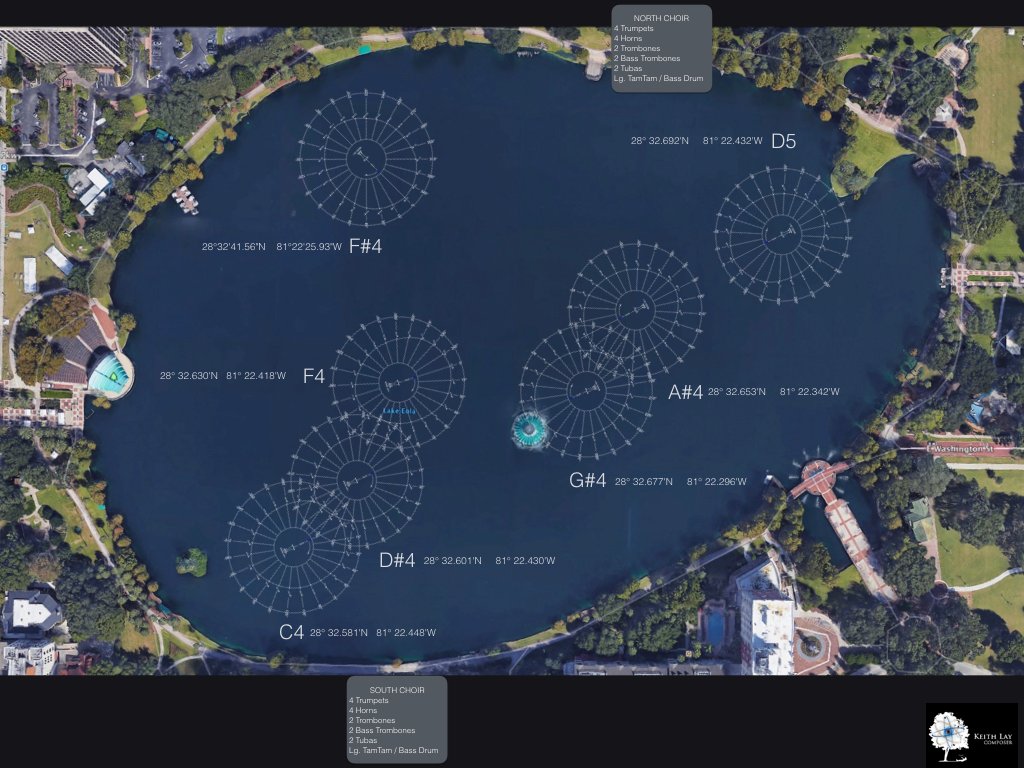

The shifting ground layer is the most prominent. It is a repeating group, or “constellation,” of notes created by a group of loud, remote-controlled, acoustic machines called “Sounders.” They each play a loud, short tone exactly together, which, moving at the speed of sound, reaches each listener in turn from closest to farthest. The constellation heard by each person comes from the length of time each note takes to get to them. Musical change of the shifting ground occurs only in the listeners’ perception by walking to a different place. A couple standing together catch a nearly identical shifting ground. The further apart the two listeners are, the less similar their constellation will be. If someone refuses to walk, they’ll hear the same constellation pattern repeated throughout. (not recommended!)

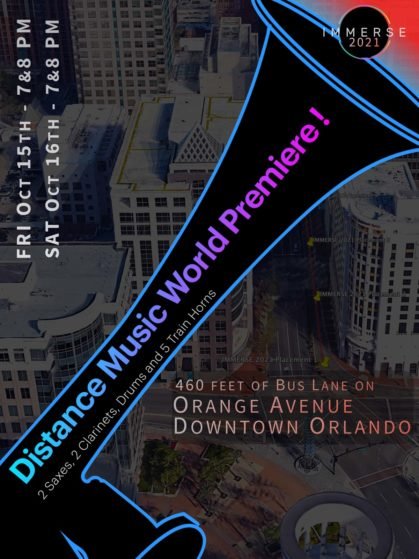

The sounders are Nathan AirChime train horns, powered by compressed air stored in heavy, high-pressure cylinders. A battery-powered telemetry system sends instructions to each sounder via digital radio.

What makes this “Music” – instead of just an engaging experiment? The answer lies in how the sounders are positioned and the inclusion of live musicians. By placing sounders at the same, exact distance apart (or doubled, tripled, etc.), every place in the shifting ground sharing those distances will have a rhythmic beat. Lots of these points exist throughout the concert area. Audiences will repeatedly find constellations with beats, gradually lose them, and then find different ones again as they walk. The composer can put a soloist or ensemble on any of these spots, and by calculating the location’s constellation, a score can be developed. They are named “musician bubbles” because hearing them over the shifting ground will only happen when they are nearby. They allow composers and performers to take full advantage of traditional composition and performance techniques for an all-around musical experience.