How to compose Distance Music

Massively Multiplayer

Every Distance Music work uses technology and the physics of sound to create a large, outdoor environment that builds a unique musical result at every different square yard of the ground’s surface. Two classes of players, multiple machines called “sounders” and multiple human musicians, create the sonic environment for the audience, who constitute the third class of multiplayer (or multi-listener). They walk through the rhythmic chaos seeking musical-metrically stable points. Sounder and musician classes are usually stationary. Because musicians don’t move, they hear a repeating phrase coming from the sounders, called a constellation. The Audience needs to move.

Defining the location

The composition begins by defining the audience-walking area(s) within the concert location. The placement of Sounders (train horns, percussion) is critical to the sound of the experience. The boundary and contents of the audience area is critical because they help define the social experience. Every installation resides within the public space of its residents and visitor and the location of important landmarks are used as location waypoints. This serves two purposes: 1) the audience knows the direction that they’re going if directed towards, say “the Civil War Statue”, and 2) focusing on those landmarks pays respect to the location’s unique features. The composition might be constructed to make that location a metrically stable point and populate it with musicians playing music from the civil war period. The shape of the audience area can vary widely. For example, in Distance Music at Lake Eola, the 0.9-mile walking path surrounded the Distance Organ, which was mounted on seven boats in the lake. At Distance Music at Atlantic Center for the Arts, the audience and the Distance Organ share the same 11-acre wooded space (except for the high-SPL safety zones around each apparatus). With inSPIRE, the audience zone was a square of pavement around which musicians were situated around them in 12 positions as far as 1200 feet distant.

Choosing a Tempo

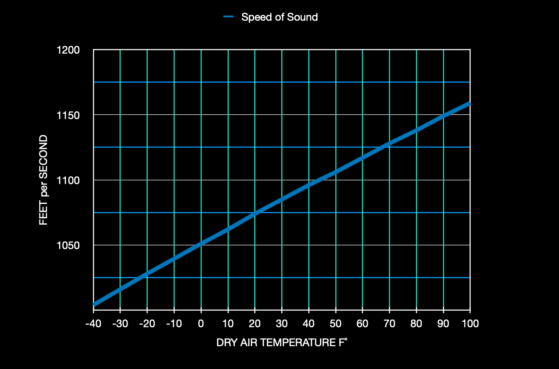

Sound moves faster in warmer air, regardless of atmospheric pressure, and a fraction more so in very humid air. For example, at 75˚F, sound travels at 141.75 ft. in a 1/8th second. At 95˚ F, that sound moves 2.75 ft. further in the same amount of time. Compounded over thousands of feet, a temperature shift of more than a few degrees could drastically change sound-arrival synchronization, threatening the presentation of the concert. In effect, colder temperatures than planned shrink the size of the composition design. From the outset of composition, research into the concert site’s average temperature for concert days will help the composer to decide the best tempo and beat division.

Choosing the Primary Interval

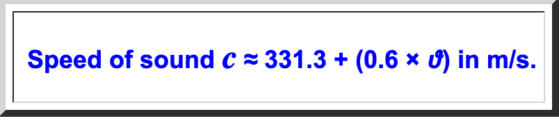

Composing Distance Music is a combination of geometric placement, harmonic taste, and choosing how the musicians will interact with the shifting ground patterns. Using Google Earth, measurements between all possible train horn placements and the prominent architectural features within the audience area are made with the goal of finding a single, least common denominator measurement between them all at a reasonable range of air temperature. This distance measurement is the “primary interval” and it is both an interval of distance as well as an interval of time. Next, the composer determines how much time sounds will take to move from each horn to each Primary Interval Point (PIP). This is accomplished by estimating the temperature of the concert atmosphere and using a formula to calculate.

C=the speed of sound in meters/sec. U =temperature in Centigrade

Once the probable speed of sound is decided, the amount of time required to travel the distance of the primary interval becomes the predominant rhythmic subdivision of the piece.

Composing the Shifting Ground

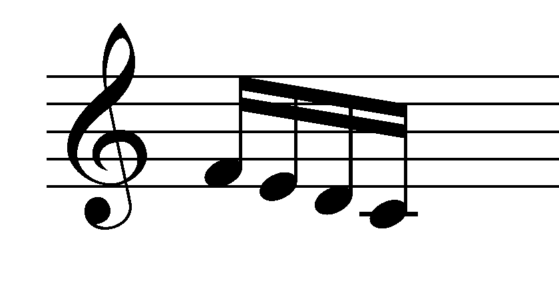

To create a specific melody to appear at a specific location, the composer first calculates the time (in milliseconds) that each note is to be heard. Then, assuming a Mode 1 presentation where all horns fire at the same moment, the horns playing each of those pitches must be placed so their sound will arrive at the correct time. For example, at 80.5˚F where the speed of sound is 1140 ft/second, three staccato notes will be heard one second apart if the second horn heard is 1140ft more distant than the first, and the, the third is a total of 2280 feet. When all three horns play their short 100ms note, the intended three-note melody will be heard at that spot. No other spot will share the same pitch order and rhythm.

Gamification: Creating points of metric coherence within Chaos

A coherent musical meter is created when all of the note entrances arrive in a simple mathematical relationship with each other. The feeling of a beat grid under any resulting melody location can only exist by deliberate design. By far, most of the constellations heard throughout the listening area will manifest in arhythmic chaos. Actively walking listeners will discern a constantly changing constellation order. Only locations that share the primary interval with all of the sounders will create a melody with meter. As many PIPs should be created as possible. As listeners near a metric point, the rhythmic pattern slowly moves from chaos to order. These points of metric stability should be composed to reside at known landmarks in the audience area so that the audience will know where to find them. If points of metric coherence are not created, then audiences will be unable to comprehend the melodic changes when they walk, and the time-space continuum will not be revealed to them.

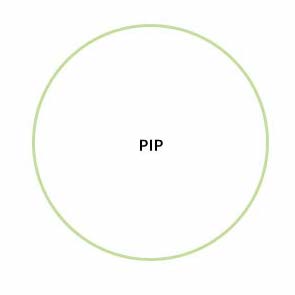

A beat will be created in the shifting ground by placing all of the horns on location points at the same distance or a multiple of the same distance (called the primary interval). Such points are called a “PIP”, or “Primary Interval Point“. Distance Music at ACA has two PIPs. Lake Eola has four.

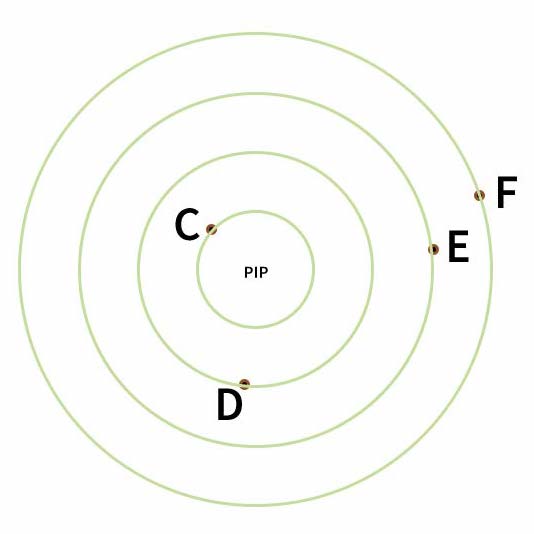

Since timing is created by distance, placing a horn anywhere on a radius will provide the same timing result. In this example, a listener at the center point (PIP) will hear the sound coming from the horn after the same amount of time, regardless of the horn’s position on the circle. This is because every point on the circle is the same distance from its center.

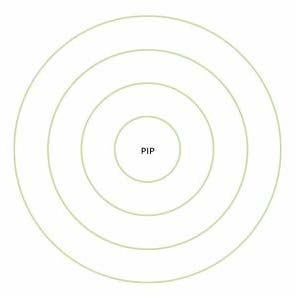

A rhythm of four evenly spaced notes will result from sound sources being placed anywhere on each of four, evenly-placed, concentric circles.

If the notes in the above example are C,D,E and F, from the closest ring to the furthest, a melody will result if the listener is standing at the PIP

Multiple PIPs

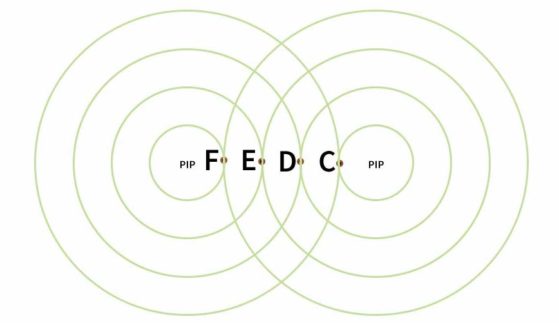

To create two PIPs, the simplest solution is to use two sets of concentric circles and place horns on their intersection points. In this scenario, audiences at both PIPs hear the same series of sounds at the same time, but in inverse order.

the Right PIP after a 16th rest

the Left PIP after a 16th rest

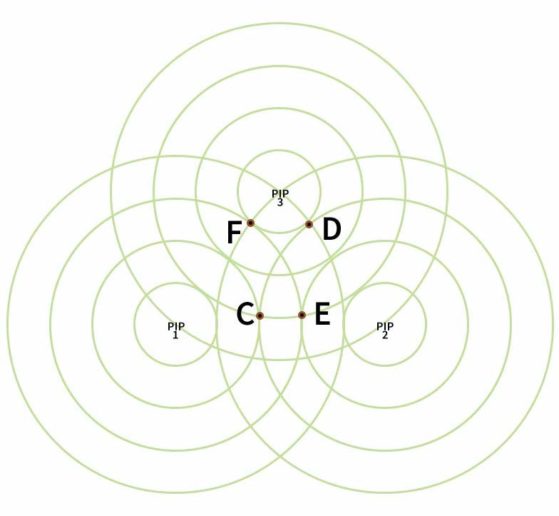

Points shared by the two sets of circles, i.e. intersection points, provide the available options in multiple PIP designs. In this example are three equidistant PIPs. When all four horns play at the same time, each PIP gets a different musical result.

Here, again, PIPs 1 and 2 are inversions of each other. Sound from horns that are equidistant to the listening point will arrive at the same time.

PIP 1

PIP 2

PIP3 contains two dyads .

PIP 3

PIP 3

Sonic Sculpture

At each staccato sounding of the horns, a kind of sonic sculpture would inhabit the concert site’s atmosphere because the shifting ground music would be “attached” to the actual walking ground. Audiences explore the sonic structure by moving, listening to the gradual permutations in the musical pattern. The melody pattern freezes when they stop moving. Those wishing to re-experience a favorite shifting ground melody can do so by revisiting that location. The acoustic time-space continuum relationship, which has been around us our entire lives, is revealed, as long as the horns continue to repeat the same initial playback sequence.

This recurring series of incessantly repeating notes could become irritating if it was the only feature of a Distance Music event. Here are some reasons this will not be the case:

- Live musicians are also a part of Distance Music concerts. The music they provide will use the shifting ground pattern as a platform to move into different tonal and rhythmic areas.

- The acoustic reflections of the horns spread across the concert site will be endlessly fascinating in itself

- The telemetry system is not limited to actuating the horns at the same time. Every apparatus is independent. Not every horn needs to fire every cycle. Also, there is another organization method I refer to as “Second Order” where the horns create metrically organized music at single, various planned points other than PIPs.