Equilateral for Four Clarinets, commissioned by Kevin Strang for the Sunshine Clarinet Quartet, is my first attempt to create music that flows on a seamless compression and relaxation of time that I call “Flowing Meter.” The quartet premiered it at ClarinetFest 2012 in Asissi, Italy.

It’s worth an extra moment to reconsider rhythm and meter to understand how Flowing Meter contributes to it:

Our universe is full of events happening all around us, the vast majority of which we have no awareness. The small chunks of the electromagnetic, mechanical, and chemical spectrums we can sense are complicated beyond comprehension. As infants, we eventually learn to find order in all of that chaos by finding patterns in our sensory input – the gestalt, like recognizing faces or identifying a herd instead of solely seeing each animal in turn. Pattern-finding in all we see and hear mitigates our fear of the unknown with a sense of order and symmetry: knowing what is around us.

What is Rhythm?

Sound happens when our auditory nerves signal our brain. As we listen, we compare it to our memory of what has just come before it, looking for organization. We use the word “rhythm” to describe qualities and relationships between the time durations between sounds we’ve heard. Natural sounds like rain, thunder, or babbling water are chaotic in their rhythms because their organizational principles exceed our grasp. They do not have a simple, memorable beat. Wind through the trees, a chorus of frogs, and birdsong: these sounds we recognize as not-human and often shut them out because of our disposition towards ordered rhythms and sounds we can remember.

What is the underlying Beat?

Our cerebellum controls voluntary and involuntary body movements, allowing us to walk, talk, stand – and stay alive by beating our hearts. Though this part of our brain is not considered a cognitive organ, its intelligence is revealed in its ease in finding the common numeric denominator in a rhythm if one exists. It’s solution to the understanding of timing is what we call the beat or pulse: a time grid on which rhythms are referenced. When you look down and find you are tapping your toes before you knew it, you see your cerebellum at work. You are ‘feeling’ the beat.

Meter

Our species’ knack for pattern-finding in all we see and hear promotes finding order and symmetry. The neatness and predictability of human-shaped environments, evident in city design, architecture, homes, and landscaping, display this normal aesthetic tendency, as does our music. Pleasure rises when a section of a rhythm pattern repeats itself because when each statement is recognized, that realization invites the listener to join it. Once aligned, we reinforce it in/with our body, moving to it. Slower tempos move with longer sections of our body that take more time to swing. Faster beats use shorter parts, like our heads or arms. We “become” the beat when we dance since we simultaneously 1) listen, 2) remember, and 3) move to the pattern. Mind and body join. The present moment manifests in the repeating rhythm. It feels larger and more spacious because the moment and what it contains is known and joined. The more complex a rhythm is, the more memory capacity each repetition requires. The next level of meta-organization is the “measure.” The number of beats within each measure is the “meter.”

What is Flowing Meter?

Flowing Meter gives us a way to create music with tempos that regularly cycle through change. Accelerando (speeding up) and deccelerando (slowing down) are new vectors added to the primary elements of meter, using standard practice notation. It is not a rejection of beat, but a sophisticated addition to it. Because it retains the cyclical nature of meter, musicians feel its shortening and lengthening of beat to correlate all of our familiar subdivisions on that curve. The result is music that flows on a seamless compression and relaxation of time.

FLOWING METER NOTATION

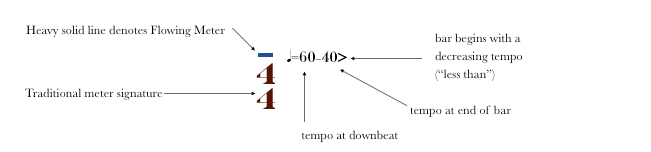

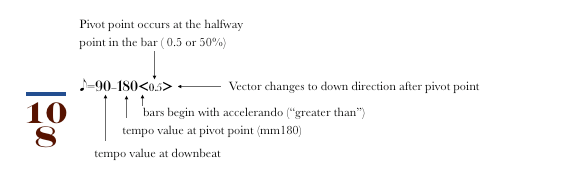

Instead of using known methods of accelerando and ritardando through an entire piece, I’ve devised a simpler notation. A horizontal line above the key signature signals the musician that the music is composed with a flowing meter in mind. Each complete cycle of tempo change takes a single bar, graphically separated with a standard bar line. A dotted bar line can be added at the maximum or minimum tempo apex in the bar, I call the pivot point. Other needed information is placed above the staff to describe the shape and detail of the flow speed and direction. Like all meter signatures, it is in force until changed by an ensuing meter signature.

Flowing Meter Notation

- The traditional meter signature still defines the number of beats and note values within a bar

- Tempo limits: the minimum and maximum metronome targets for each bar

- Vector: is the direction of tempo increase or decrease. The vector(s) are notated by the use of “<” less than or “>” greater than symbols. Flowing meters tempos are shaped either faster|slower, or slower|faster

- Two tempi limits are always specified on each side of the vector sign. Above them, a number less than 1 acts as a “coefficient” that indicates the pivot point placement in the bar. The total number of beats in the bar is multiplied by that number to define the location. A dotted or dashed barline can be used to graphically place this point in the music. If no coefficient is written, then it is assumed to be a .5, placed in the very middle of the bar.

The above example has one vector: bar begins at mm.60 and slows (“>”) to mm.40, creating a sawtooth shape. This is used in the second movement “Sawtooth: Slanted Calliope”.

For this example, the musicians start the bar at mm90 and accelerate to mm180 at the 6th eighth note (pivot point, halfway through the bar), after which they decelerate back to mm90 by the next downbeat. Bars containing two vectors are more comfortable to play if a dotted bar line is inserted at the pivot point. Such a dotted line provides a mental ‘target’ for the ensemble to reach while performing.

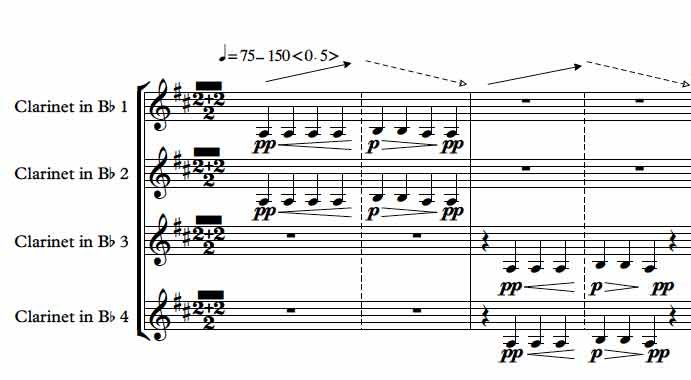

A symmetrically balanced accelerando and decrescendo are employed in the first movement, “Equilateral”. The “<.5>” figure places the pivot at 50% in the bar. A dotted bar line at the pivot point helps musicians visualize the apex resulting in tighter ensemble performances.

listen